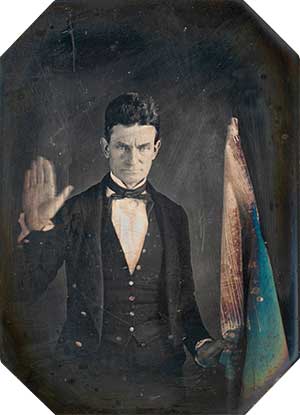

There are several links between Canton, Connecticut and the famous John Brown of the abolitionist raid on the Federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia.

Perhaps the most significant is his family heritage. Brown’s grandfather, also named John, was a captain in Colonel Pettibone’s regiment of the Connecticut State Militia. Unfortunately, as so many soldiers did, Captain Brown acquired severe dysentery and died.

The widow, Hannah, who shortly delivered her eleventh child, tried desperately to maintain the farm and keep the family together; however, even with the help of two borrowed slaves, the severe winter of 1777-78 was too much for her. She was forced to place most of her children in the homes of neighbors, keeping only the younger ones with her on the farm. One son, Owen, age 5 at the time of his father’s death, later went to live with the Congregational minister of West Simsbury, Reverend Jeremiah Hallock. He absorbed much of Reverend Hallock’s strict Calvinistic theology as Hallock was known for his anti-slavery opinions and Owen undoubtedly also, in later years, passed these convictions on to his own children.

Owen Brown, in 1793, married a local girl, Ruth Humphrey Mills. The young family moved to West Torrington, where in 1800 a son, John, was born. Owen eventually migrated to the Western Reserve in Ohio, where he became quite successful as a cattle and sheep raiser. At one point he resigned from the Board of Trustees of Western Reserve College because the group refused to admit a Negro to the school. He became active as a trustee at Oberlin College, the first such school to admit both Negroes and women. Lessons learned in his West Simsbury youth continued to influence the adult Owen Brown, and surely were evidenced to his young children.

The boy, John, followed his father’s footsteps, herding sheep and cattle, tanning hides and sorting wool. In his late teens he expressed a wish to become a Christian minister, so Owen sent him east to see Rev. Jeremiah Hallock in West Simsbury for advice. Hallock referred him to his brother, Rev. Moses Hallock, who had a small seminary in Plainfield, Massachusetts. John began his studies there, but after a few months transferred to Morris Academy in Litchfield, Connecticut. Illness and lack of funds contributed to his abandoning his studies and returning to the tannery business in Ohio.

In succeeding years John Brown married twice and fathered twenty children, nine of whom died at an early age. He failed in business innumerable times and moved about in the states of Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York. Along with his father, John was active in radical abolitionist groups and helped many escaped slaves pass along the “underground railroad.” In 1846 he started a wool-sorting business in Springfield, Massachusetts. Springfield’s proximity to Canton, Connecticut, occasioned several visits to Brown relatives and the old family homestead.

The repeal of the Missouri Compromise and the enacting of Stephen Douglas’s Kansas-Nebraska Act aroused the ire of the abolitionists like nothing previously had done. By this legislation Congress turned over the decision for or against slavery in new states to the inhabitants of those territories. Pro-slavery men from adjacent Missouri entered Kansas and voted to seat an illegal legislature. John Brown and several of his sons became very involved in the bloody clashes that then arose, even to the extent of murdering five proslavery settlers. Frederick, one of John Brown’s sons, was killed in these skirmishes.

To help finance the purchase of weapons Brown returned east to give lectures on his experiences. At least one of the talks was given in Tiffany Hall, Collinsville in the spring of 1857. While in Canton he stopped by his father’s birthplace and picked up the gravestone of his grandfather, Captain John Brown. There was still some space left on the stone, so he sent it to his home in North Elba, New York “to be faced and inscribed in memory of our poor Fredk who sleeps in Kansas.” He wrote to John, Jr., “I value the old relic much the more for its age and homeliness; & it is of sufficient size to contain more brief inscriptions. One hundred years from 1856 should it then be in the possession of the same posterity: it will be a great curiosity.” This Canton Center stone does include John Brown’s name as well as Frederick’s and is today encased in glass at the Brown homestead in North Elba. A more elaborate memorial stone to Captain John and Hannah Brown can be seen in the Canton Center cemetery.

The culmination of John Brown’s abolitionist career at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia also had a connection with the town of Canton, as reported in The Collinsville Star Nov. 9, 1859, where Charles Blair, the forge master of the Collins Company of Collinsville explained his connection with the supplying of pikes for the Harper’s Ferry raid.

“It seems that John Brown stopped here one night in Collinsville in the latter part of February or March 1857. “Old Brown”, as he was familiarly called, came to this town to visit his relatives (most of whom, I learn, reside here) and by invitation addressed the inhabitants at a public meeting. At the close of the meeting, or on the following morning, he exhibited some weapons which he claimed to have taken from Captain H.C. Pate at the battle of Black Jack. Among others was a bowie knife or dirk having a blade about eight inches thick. Brown remarked that such an instrument, fixed to the end of a pole about six feet long, would be a capital weapon to place in the hands of the settlers of Kansas to keep in their cabins to defend themselves against any attack by ‘Border Ruffians’ or wild beasts, and asked me what it would be worth to make one thousand. I replied that I would make them for one dollar each, not thinking it would lead to a contract, or that such an instrument would ever be wanted or put to use, in any way, if made.”

In sworn testimony before a Senate investigating committee after the capture and hanging of Brown, Blair later gave more details of the manufacture and shipping of the pikes: “I think he went to Springfield, Massachusetts, before a bargain was made between us; at any rate, the result was that I made a contract with him. I think he ordered me to make a dozen as samples, and I had forwarded them to Springfield.” Blair described the method of payment and time limitations on the written contract. He agreed to make a thousand pikes at one dollar each. Blair added, “He paid me $350 within ten days. This advancement was made in the latter part of March, 1857. I then went and purchased my materials. I went to a handle-maker in Massachusetts and engaged him to make a thousand handles. I purchased the steel for the blades and set a man forging them out, and he forged out perhaps five hundred of them.” A long-time Collins Company employee, Horace G. Brown (no relation to John), years later recalled that he had worked on the pikes ordered by John Brown, who, he said, “was a frequent visitor and guest of Charles Blair.”

Brown sent more money to a total of $550 and Blair continued work on the pikes until several days after the expiration of the thirty days in which a second installment of money was to come. He explained, “—receiving no further funds from Mr. Brown, I stopped the thing right where it was, determining that I would not run any risk in the matter. I just laid it aside, and there it lay, the work in an unfinished state, the handles stored away in the store-house, the steel which I had purchased stored away in boxes, the few blades which I had forged were laid away.” Blair stated that he had never finished any of the pikes and considered the contract at an end. Then, unexpectedly, Brown appeared in Collinsville on June 3, 1859 saying he could at last fulfill his contract with Blair. Blair explained that he was now too busy to do the work and remarked, “What good can they be if they are finished; Kansas matters are all settled, and of what earthly use can they be to you now?” “Well,” Brown replied, “they might be of some use if they were finished up,” and that he could dispose of them in some way, but as they were they were “good for nothing.” Blair then said, “I will receive of you the remaining $450, if you have it and wish to pay it to me, and if I can find a man anywhere in the vicinity that is accustomed to doing such work who will finish up the work, I will do so, provided I can do it and come within the means, and it will not be much trouble to me.”

Brown paid him $150. A few days afterwards Blair received a letter dated, Troy, N.Y. June 7, 1859, with a draft enclosed on a New York bank for $300. Soon after Brown left Collinsville, Blair agreed with C. Hart & Son of Unionville, Conn. to finish up the pikes which had been commenced in 1857 and also to make 450 more – making in all about 950. In July, Blair received a letter from Brown directing him to send the “freight”, when ready, to J. Smith & Sons, care of Oakes and Cauffman, Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.

Blair’s testimony continued: “When they were done, I saw that the blades were tied up in boxes, and the handles in bundles. I simply marked them according to the directions. Then the next letter I received was dated September 15, acknowledging the receipt of the goods. That is the whole story, I believe.” When questioned about the reason for the change in destination, Blair replied, “I got the impression that they were on their way to Ohio or to the West, and having always had in my mind the idea that they were first originally destined for the West, I did not know but that he might send them, and that Oakes and Cauffman, as I supposed, were forwarding merchants, and J. Smith & Son, I supposed, were a bona fide firm. Since further developments have come out, it appears who J. Smith & Sons were, but I certainly knew nothing about it at that time.”

Apparently this testimony satisfied the Congressional committee that Blair was innocent of any complicity in the Harper’s Ferry affair. The Collins Company’s name was never mentioned, although half of the pikes were forged there. As the Collins Company had large contracts for tools in the Southern states, it was important that the company not be implicated in any dealings with militant abolitionists.

Subsequent history of the pikes reveals that none of them ever reached the hands of any freed slaves, although John Brown himself was armed with one of them when he was captured. About half of them were found on a cart at Harper’s Ferry and were quickly appropriated by souvenir collectors. The remainder, still at the farmhouse in Maryland where the conspirators had left them, were sent to the Federal Armory in Richmond, Virginia, where they were captured by the Confederacy at the onset of the Civil War. There is some evidence that they may have been used by the Confederate cavalry. A few were used by both North and South as propaganda tools. Wendell Philips regularly exhibited a John Brown pike at his anti-slavery lectures, and Edmund Ruffin, the fiery Southerner who fired the first shot at Fort Sumter, had a use for them, too. He acquired fifteen of the pikes and sent one to each Southern governor and some Congressmen with an explanation of its purpose. His label read, “Sample of the favors designed for us by our Northern brethren.”

There is no evidence that members of the Brown family living in Canton were involved in any of this and, in fact, they seem to have regarded John as somewhat of a lunatic. Two rough forgings of the “Brown pikes” were preserved in the safe of the Collins Company for over 100 years; one of these is now in the Canton Historical Museum and the other in the Connecticut Historical Society. At the Brown home and museum in North Elba, New York, there are two different styles of “Brown pikes”, presumably one kind forged in Collinsville and the other in Unionville. At least one of the twelve sample pikes has been discovered in the hands of a family in the Chambersburg, Pennsylvania area. It is likely that this was found among the others after the Harper’s Ferry raid and kept as a souvenir of that important inciting event related to the American Civil War.